For months, I’ve been deep in the trenches with AI, using it to amplify my work on responsible AI initiatives, manage complex projects, and automate the routine tasks that used to eat up my days. But this week at the Utah AI Summit, I did something different. I zoomed out.

Watching public sector leaders, industry executives, nonprofit directors, and academics fill the Salt Palace Convention Center for honest conversations about AI’s impact on society, work, and equity reminded me why I do this work. This wasn’t performative. This was the hard stuff: jobs, education, data ownership, and how we make sure no one gets left behind.

The moment that stopped the room, though, came from an unexpected voice.

When the Russian Literature Major Stole the Show

President Astrid Tuminez of Utah Valley University opened her remarks to the education panel with a disarming introduction. She majored in Russian literature, she said, and was super prepared for the world of AI.

Here was a university president running a campus with 48,000 students, leading with the humanities, not the technical specs.

I was sitting at a round table near the center of the room with members of the nonprofit community including Craft Lake City and Slug Magazine. When one of the more petite and unassuming panelists of the day captured the room, we all leaned in to hear what this sage had to say. I thought: I want to have lunch with this woman someday and get into a deep discussion with her. This is what I’ll remember when I reflect back in months or years.

When pressed later about the NVIDIA partnership (which she declined to discuss, noting there was already a press release), Tuminez pivoted hard. She referenced a recent tragedy on the UVU campus and asked a question that cut through the technical optimism filling the convention center: Would AI have been the best solution to prepare students to complete their studies and go into the workforce after something like that?

Her answer: Russian literature.

Dostoevsky taught her that “my hallelujah is born from a furnace of doubt.” Solzhenitsyn reminded her that “the line of good and evil cuts through the heart of every man.” These weren’t just literary references. They were her framework for understanding what humans need in crisis: connection, resilience, problem-solving capacity, the ability to have difficult conversations, to iterate when you feel you’re in hell and figure out how to get out.

That’s not the machine, she said. That’s the human.

She mentioned reading an MIT Technology Review article on the way to the summit about churches using AI for pastoral care, profiling congregants with biometrics to better minister to their souls. The irony wasn’t lost on her. We’re using the most sophisticated technology to try to address the most human needs.

Her closing advice? After Vic Eager warned about leaning in too far, Tuminez addressed Scott Pulsipher directly: “Dance while you’re at it.”

I scribbled “DANCE!” in my notes with three exclamation points. Once again this small but fierce leader said the most important and memorable thing amongst a conversation that kept threatening to get too serious, too technical, too focused on optimization. Tuminez just kept pulling it back to what matters.

The Education Conversation: Beyond Technical Training

The education panel brought together university presidents, community college leaders, workforce development specialists, and Tech Moms founder Trina Limper. The conversation kept returning to a central tension: how do you prepare people for jobs that don’t exist yet while also protecting them from technology’s potential harms?

Western Governors University President Scott Pulsipher built on Tuminez’s remarks by quoting C.S. Lewis: the most sacred thing presented to your senses is your neighbor. That human-centered principle, he argued, must drive how institutions think about AI integration.

WGU is shifting from being digitally native to becoming AI-native. If the internet democratized access to education, AI will democratize learning itself. Learning models can become radically personalized, adapting to how each student traverses subject matter and develops competencies.

But Pulsipher offered a warning that resonated beyond education: if you’re only applying AI to tasks and activities you currently do, you lose. You have to think about what AI enables that you couldn’t do before. Applying AI solely for efficiency means you need fewer people doing the same tasks. That’s not a winning strategy for students or society.

Tuminez had established UVU as what she called a “practice laboratory for AI” through their Applied AI Institute, which recently received a $5.2 million grant. The approach includes deploying 24/7 teaching assistants in the top 30 most-enrolled courses, training faculty (because if they’re scared, they won’t use it), and incentivizing students from any major, philosophy and Russian literature included, to get certified.

Her insight about her Microsoft years rang through the conversation: the important questions weren’t about engineering, though those mattered. They were about understanding the psychology of humans, the sociology of human behavior. Technology succeeds or fails based on whether it serves human needs.

Salt Lake Community College President Greg Peterson emphasized teaching competencies rather than specific tools. Aviation maintenance students learning to use technology to predict wear and tear on airplane equipment, physical therapy assistant students using AI tools for clinical documentation, lab technicians leveraging AI to troubleshoot chemical equations, the pattern is consistent: teach the capacity to problem-solve with changing tools, not mastery of today’s specific technology.

Trina Limper from Tech Moms addressed the workforce crisis head-on. Entry-level positions have dropped 22-28%. Where do you train people? Where do you place graduates? Tech Moms runs over 50 cohorts across Utah, serving thousands of women transitioning into tech careers. The answer, she argued, isn’t in the technology itself. It’s in teaching people how to learn.

Her framework echoed the education panel’s consensus: AI plus EI (emotional intelligence). Dealing with ambiguity. Building organizations that can move quickly. Focusing on the human-centered side. “Don’t lean in alone,” she urged. “Bring somebody along with you. Everyone in this room can be an influencer. Tap someone on the shoulder and say it’s easier than ever to learn.”

The transformation doesn’t just affect thousands of women returning to work. It affects their families, their kids. “You want to solve K-12 STEM?” Limper asked. “Get the moms in tech.”

Vic Eager from Talent Ready Utah added a crucial caution: lean in, but don’t fall over. Industry keeps collapsing jobs without building succession. When attrition happens, there’s no bench. “Don’t stop building your bench,” he warned.

The Contradiction We’re Not Talking About

Here’s the uncomfortable irony: while the Utah AI Summit panelists emphasized that humanities, philosophy, and social sciences are essential to responsible AI development, Utah’s Legislature is actively defunding those exact programs.

This summer, the University of Utah cut 81 academic programs; including theater, dance, foreign languages, and multiple humanities degrees; under a legislative mandate to eliminate “inefficient” majors with few graduates and lower-paying career paths. The directive came with $60.5 million in higher education cuts, targeting programs that don’t directly lead to high-wage jobs the state needs.

Most cuts hit the College of Humanities (22 programs) and College of Fine Arts (8 programs). Master’s degrees in ballet and modern dance, gone. German teaching degrees, gone. Ph.D. in theater, gone. The message: if it doesn’t immediately drive economic growth, it’s expendable.

But at the AI summit, President Tuminez; who leads a campus where these cuts are happening; stood in front of industry leaders and policymakers and said Russian literature prepared her better for AI leadership than engineering would have. She quoted Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn to explain human resilience, connection, and navigating crisis. Scott Pulsipher emphasized C.S. Lewis on human-centered values. The entire education panel kept returning to the same theme: domain expertise in how humans think, behave, struggle, and connect matters more than technical AI skills.

Matthew Prince sent Aristotle’s Politics to Anthropic’s founders before joining their board. Chris Malachowsky talked about understanding human psychology and sociology. Every speaker emphasized that AI amplifies whatever we bring to it; and what we need to bring is deep understanding of human behavior, ethics, philosophy, and culture.

Yet Utah’s policy literally defunds those exact disciplines while simultaneously hosting summits about why they’re essential. The Legislature wants high-wage STEM degrees. The AI leaders are saying we desperately need philosophers, humanists, and social scientists to make sure AI doesn’t just make us more efficient at being less human.

I’m sitting here thinking about my own kids coming home from university this week. What do I want for them? Technical skills, sure. But more than that; I want them to be able to think critically about power, meaning, ethics, what it means to be human. The same shit Dostoevsky was wrestling with. And Utah’s literally defunding the programs that teach that.

The disconnect isn’t just awkward. It’s dangerous. If we train people to build and deploy AI without the humanistic frameworks to understand its impact on society, dignity, power, and meaning, we’re not building a “pro-human” AI future. We’re building a technocracy that treats efficiency as virtue and everything else as overhead.

The Policy Framework: Enabling, Not Obstructing

While education dominated the emotional center of the summit, Utah’s policy approach provided the structural foundation. The state became the first to establish an Office of AI Policy, but what makes it interesting is how they’re doing it.

Instead of prescriptive regulations, the AI Policy Lab has authority to enter into mitigation agreements with businesses. Companies can approach the lab when they’re worried about operating in gray area or potentially breaking regulations. The lab can exempt them from particular regulations, limit their liability, or suggest pilot programs with restricted scope. Then the lab learns from those agreements and makes policy recommendations to regulators and the legislature.

The mental health chatbot bill emerged directly from this process. Rather than regulating AI development at the model level (which other states like Colorado and California are attempting), Utah focuses on consumer-facing applications within traditional state jurisdiction.

The philosophy: regulate use cases and applications, not underlying model development. Let innovation move while protecting citizens. Learn in public. Iterate based on what actually happens, not what might happen.

Honestly, this is the kind of pragmatic approach I wish I saw more of; not perfect, not trying to predict every scenario, just “let’s try this and learn.” It’s basically the startup mentality applied to policy. Which feels wild coming from government, but also kind of refreshing?

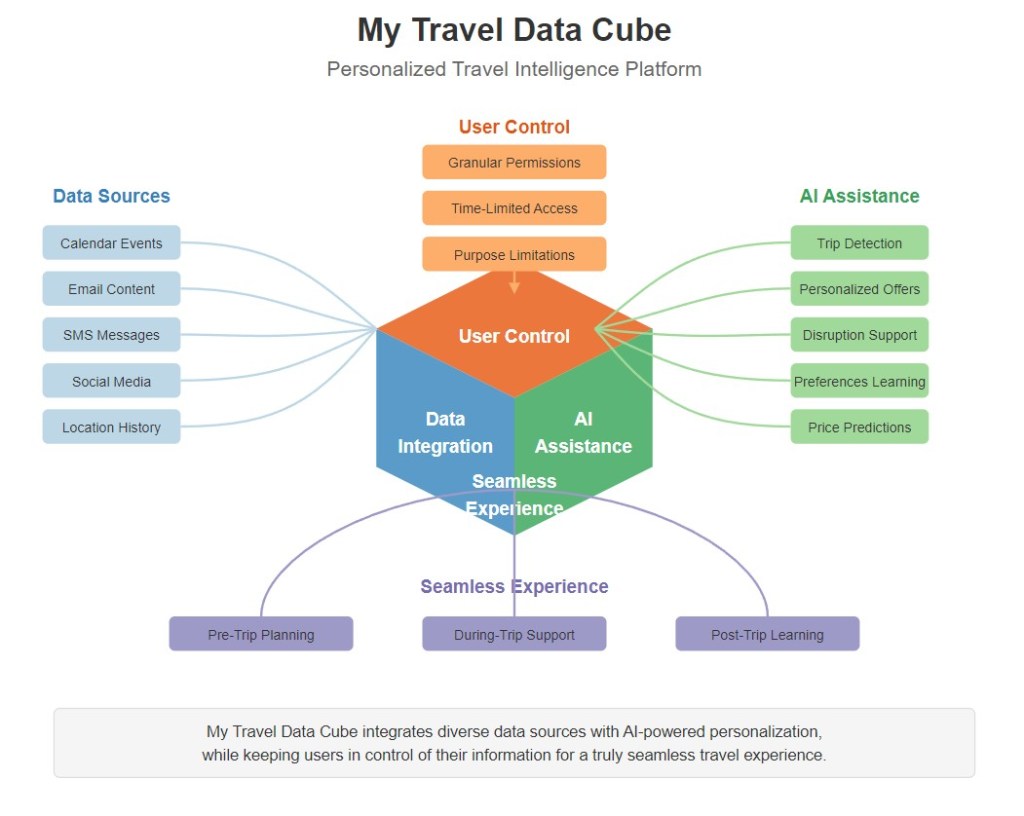

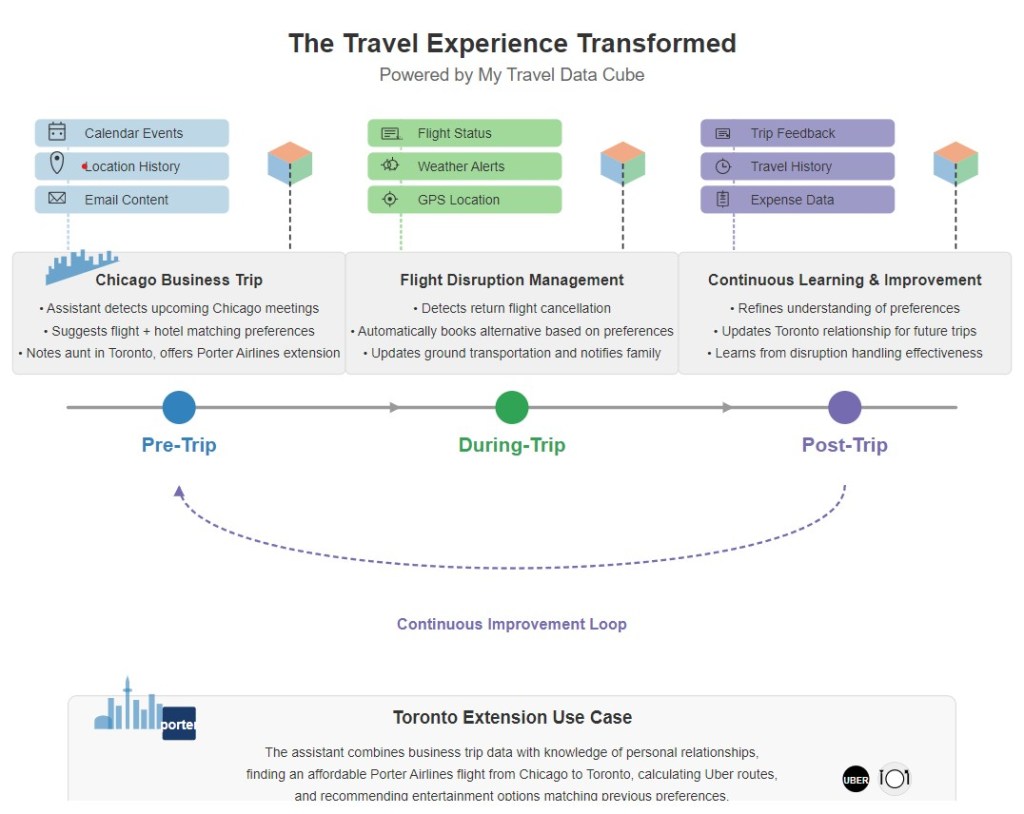

Data Sovereignty and Context Engineering

One panelist made the case that context engineering matters exponentially more than prompt engineering. If you ask an AI about your recent blood test results, it will hallucinate because it lacks context. All the data that makes up our lives sits dispersed across corporate servers. Those companies own that data, not individuals.

The vision: humans should own their own LLM, their own locally hosted open-source model on their own device, with all their own context. Not surveillance capitalism. Not surveillance governments. Individual agency and control.

Utah’s Digital Choice Act represents early movement toward this model. The approach recognizes that competitive advantage in the AI era won’t come from whether you use AI, but from how well you apply it, and who controls the context that makes AI truly useful.

Trust as Essential Infrastructure

Matthew Prince, Cloudflare CEO and Park City native, brought Aristotle’s Politics to the conversation. At scale, technology companies act almost governmental in their influence. Aristotle identified three requirements for governmental trust: transparency, consistency, and accountability.

You must know what the rules are. The same rules must apply the same way to people in the same circumstances. The people who write the rules must be subject to the rules themselves.

Prince argued many technology companies learned wrong lessons, defaulting to radical secrecy from the Fairchild Semiconductor playbook. At Cloudflare, when they make mistakes, they explain exactly how. They’re in the trust business.

He also issued a stark warning about AI doomerism. Much of the catastrophic messaging, he argued, comes from AI companies themselves. When Anthropic appears on 60 Minutes saying people should be scared, they’re pitching to be regulated in ways that create ring fences around their position. If regulation requires massive datasets that only a few companies possess, the future becomes five AI companies, not 500,000.

The trust deficit is real. The Edelman Trust Index shows declining trust in both government and corporations. In an AI-saturated future, trust becomes the essential infrastructure. Transparency isn’t optional anymore.

Prince was surprisingly nuanced and articulate on this stuff; he sounded a bit more like the owner/editor of a mountain town newspaper (which he is incidentally). You could tell he’s thought about it deeply, not just doing the CEO talking points thing. But I kept thinking: is anyone from the Legislature actually hearing this? Are they making the connection between “we need trust and transparency” and “we just gutted the humanities programs that teach people how to think about trust and power”? The cognitive dissonance is exhausting.

What made the summit work was the density of authentic collaboration; Governor Cox, state legislators, university presidents, industry leaders, nonprofit directors all in the same space, working through hard problems in public. Disagreements happened, but they were productive disagreements rooted in shared goals. Senator McKinnell noted that when Utah worked on social media laws, the team included the Governor’s Office, Division of Consumer Protection, Department of Commerce, and House and Senate leadership; top to bottom collaboration without territorial behavior.

Moving at the Speed of Trust, Dancing While We Do It

Chris Malachowsky, NVIDIA co-founder, closed his keynote with a principle that captured the summit’s theme: the work ahead is about creating a deliberate future, not a future that just happens to you. The investments, the energy, the thought he saw throughout the day pointed toward intentionality.

That deliberate future requires something that can’t be automated: trust. Trust between sectors. Trust between policymakers and entrepreneurs. Trust that regulation will be thoughtful rather than reactive. Trust that innovation won’t sacrifice human dignity and agency.

AI will reshape work, education, healthcare, and civic life. The possibilities are genuine. So are the perils. The question isn’t whether we’ll have AI-saturated systems. The question is whether we’ll design those systems with intention, with input from philosophers and social scientists alongside engineers and investors, with mechanisms that protect individual rights while enabling innovation.

Tuminez’s moment crystallized this. A Russian literature major who worked at Microsoft for six years, now running a university becoming an AI practice laboratory, quoting Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn while advocating for technical training across all majors, reminding a room full of technologists and policymakers to dance while they’re building the future.

That’s the work. Building systems that amplify human capacity while protecting human dignity. Moving deliberately while maintaining joy. Leaning into the technology without falling over. Bringing people along rather than leaving them behind.

Utah’s betting on collaboration, adaptive policy, and centering human flourishing rather than technological capability. Whether that bet pays off will depend on sustained commitment to moving at the speed of trust, dancing all the while.

The question for other communities: What conversation are you having? And who’s in the room when you’re having it?

A Personal Note: Where the Real Magic Happens

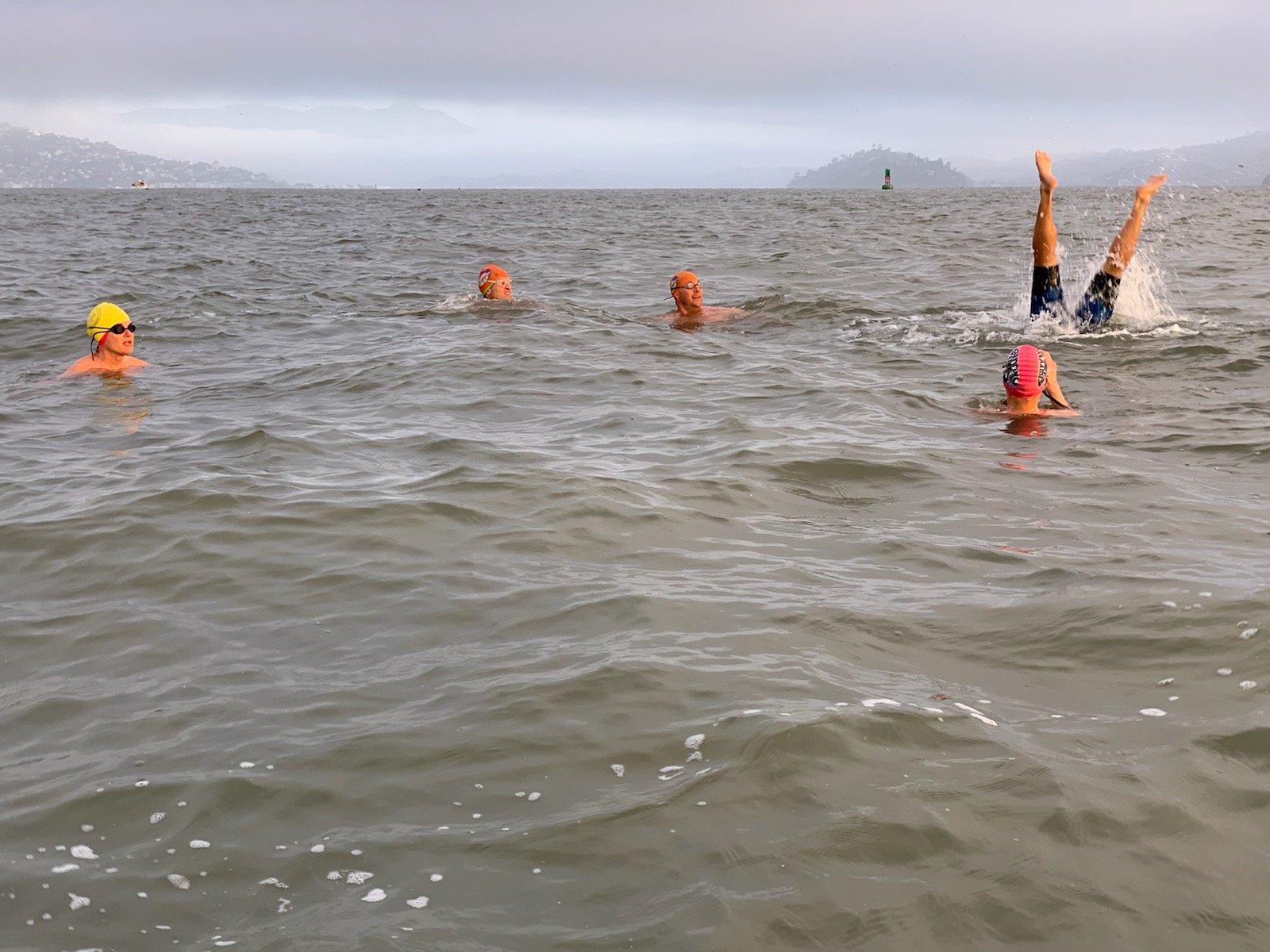

This has been an amazing week of deep thought, conversation, and work productivity amplified by AI research tools. But I once again need to zoom out and remind myself that the real magic moments were those centered around human connection. None of the learnings and productivity outcomes would have happened, or meant anything profound, without the context of the people I met and entered into dialogue with.

If I had to choose between the AI tool assistants or the human-centered connections I had this week, the human connection wins out by a mile.

At lunch I got talking with someone in the sponsor lounge about my startup project. Turns out he’s a good friend of a former colleague and volunteers with blind skiers at the National Ability Center; same place I teach adaptive skiing. That connection will outlive this conference. Another reminder that human intelligence and serendipity still matter.

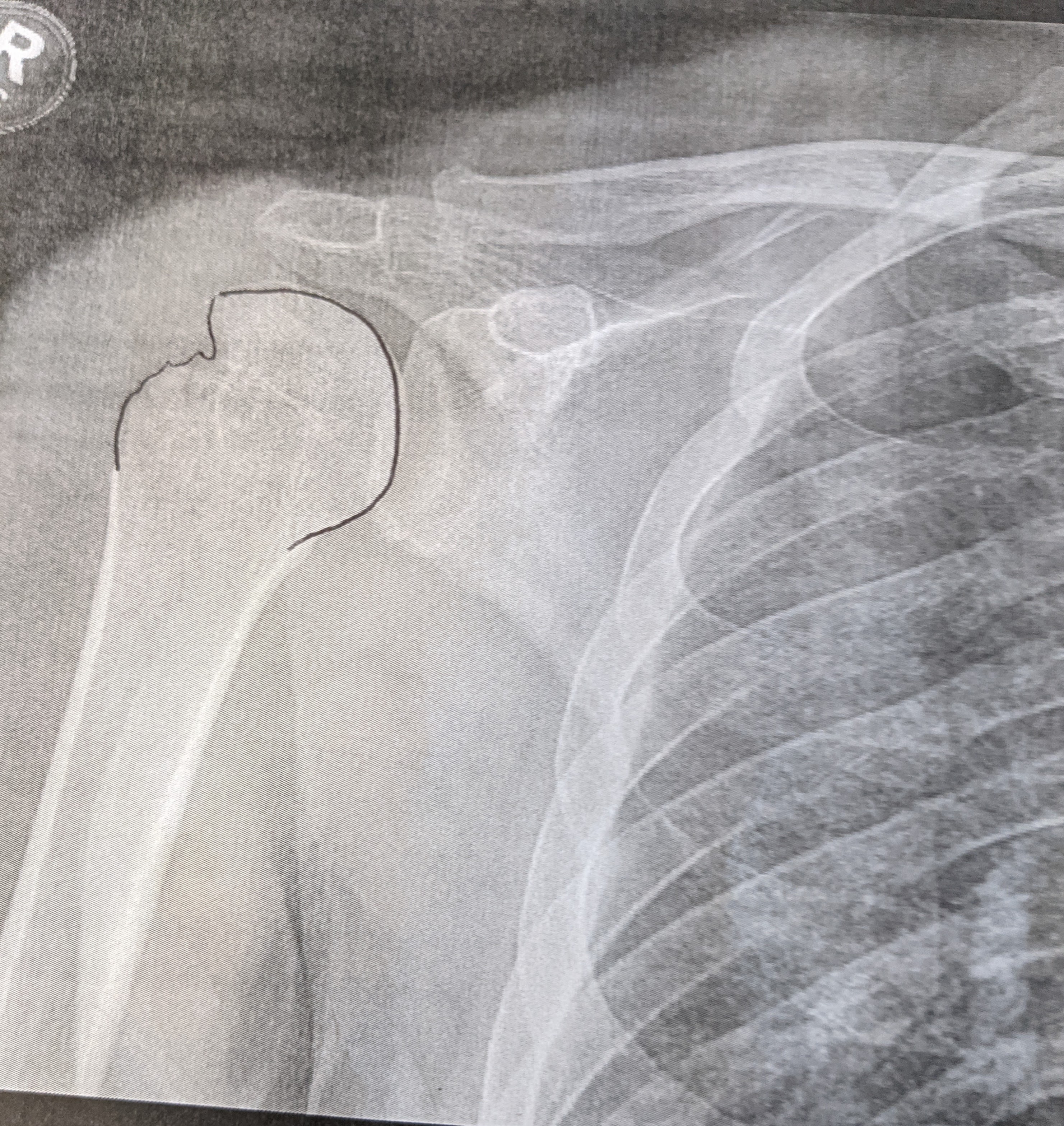

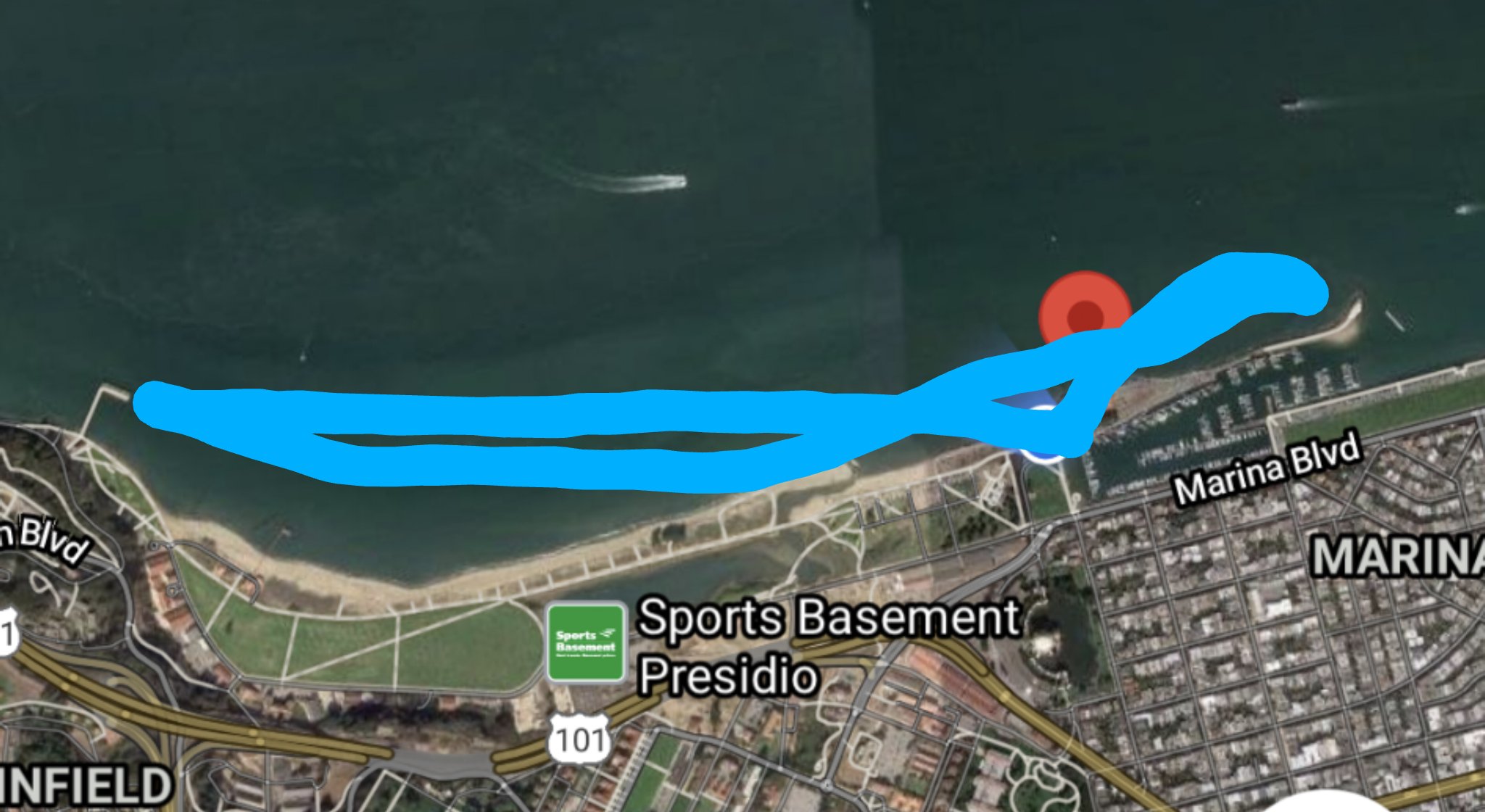

But all of this growth is really minuscule if I don’t carve out time this weekend to embrace the awe of nature and the physical feeling that can only come from getting your heart beating while recreating. Most importantly, I must make sure to step back from this hyper growth and learning phase around AI to be truly present with my family when my children arrive home from university on Friday.

This self-awareness is really the proof that I am human. The AI, that mathematical and statistical probabilistic machine, can only know this if I tell it or train it to keep these values at the top of the pyramid for me. Let’s hope the humans always stay in the loop and also recognize that AI is simply a tool. We must use that tool responsibly and with an ethical framework.

Seth is a member of the One U Responsible AI Community Committee, a part-time Adaptive Ski Instructor at the National Ability Center, and is working on an early-stage tech startup project.

Disclosure: This article was created in collaboration with Claude.ai as a writing and research partner. All perspectives, experiences, and opinions are my own.